“Control your perceptions. Direct your actions properly. Willingly accept what’s outside your control.”

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- What is a spin-off?

- How does spin-off accounting work?

- What specific biases are reflected in a spin-off company’s financials?

- How do these biases affect the quality of financial reporting for spin-offs?

- What do the empirical results show?

- Why is this information relevant for fundamental investors?

- Where can fundamental investors gain an edge?

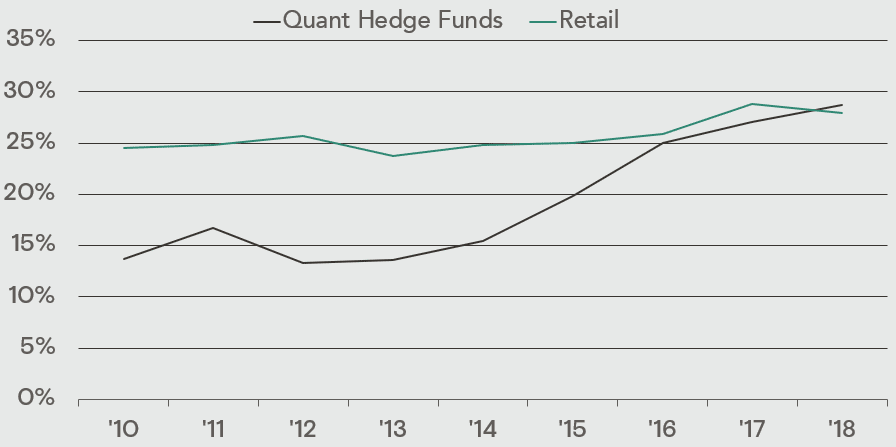

It’s no secret that fundamental investing is a dying art. The WSJ recently reported that “Roughly 85% of all [U.S.] trading is on autopilot — controlled by machines, models, or passive investing formulas…” In other words, less than 15% of daily trading volume is driven by actual people using fundamental strategies. “Quantitative hedge funds, or those that rely on computer models rather than research and intuition, account for 28.7% of trading in the stock market…a share that’s more than doubled since 2013,” says the Journal. “They now trade more than retail investors, and everyone else” (CHART 1). How could ordinary human investors possibly gain any advantage over their highly sophisticated machine counterparts? Perhaps they could start by closely following corporate spin-offs. I’ll explain why below.

CHART 1: U.S. Share Volume by Fund Type

Source: WSJ.

The stock market serves as a real-time mechanism for price discovery. The market is a place where competing buyers and sellers absorb new information about a company and collectively determine the precise balance point (i.e., price) where supply equals demand. However, this price-setting process is made more complicated in the case of corporate spin-offs, when investors must assess a company’s worth using “best estimate” financial statements that may have never existed before and only extend a few years into the past. A recent piece entitled “Carve-out Earnings Quality in Corporate Spinoffs” (written by Zac Wiebe, Assistant Professor at the University of Arkansas) highlights many biases associated with the accounting methodologies used to create spin-off financial statements. Wiebe identifies several reasons why historical spin-off financials are usually poor indicators of future earnings/cash flows. Thus, it follows that algorithmic trading strategies — which simply extrapolate historical financial data into the future — should have a difficult time accurately appraising what a spin-off company is truly worth. Therein lies a unique opportunity for active investment managers who are interested in gaining a leg up on today’s machine-driven market.

I’ll first provide a general summary of Wiebe’s academic piece by answering five questions listed below. Then (and most importantly), I’ll conclude by explaining how Wiebe’s research suggests that human investors analyzing spin-offs are likely to uncover price/value dislocations — giving these investors a rare advantage in a market environment where the majority of asset prices are robotically determined.

- What is a spin-off?

- How does spin-off accounting work?

- What specific biases are reflected in a spin-off company’s financials?

- How do these biases affect the quality of financial reporting for spin-offs?

- What do the empirical results show?

What is a spin-off?

A corporate spin-off (spinco) happens when a firm divests one of its subsidiaries by standing it up as an independent public company. Instead of receiving cash proceeds for selling the subsidiary, the “parent company” (remainco) simply distributes to its existing shareholders a 100% equity interest in the newly created spin-off company. Perhaps one of the most enticing attributes of spin-offs is the fact that they are generally tax-free in the United States (subject to certain IRS requirements).

Stay up to date

Subscribe to receive our quarterly investor letters and market updates.

How does spin-off accounting work?

As Zac Wiebe points out in his piece, the behind-the-scenes accounting work done in preparation of a spin-off is quite complex. “Carve-out financial reporting in spinoffs is highly discretionary because the statements cover preceding reporting periods when the spinco did not exist as a separate legal entity,” writes Wiebe. He continues: “In accordance with SEC requirements, parent companies planning spinoffs must provide audited financial statements for the spinco…including two balance sheets and three income statements. This process is difficult because the spinco often has no financial reporting structure, and usually did not exist as a separate legal entity for the periods in question. Thus, financial statements for the spinco must be ‘carved out’ of the consolidated statements, which involves a great deal of judgment by parent company managers.”

In practice, carve-out accounting for spin-offs does not necessarily require the creation of a brand-new set of historical financial statements from scratch. Today it is quite common to see large companies spin out parts of their business that were previously classified as “reportable segments” under ASC 280. In such cases, investors will find that key metrics in the spinco’s carve-out financial statements (like revenue and operating profit) closely match actual historical figures reported by the parent company at the segment level. “Former segments have additional pre-spinoff financial reporting processes relative to non-segments,” writes Wiebe. “Carve-out reporting for former segments involves less management discretion, thereby constraining opportunistic reporting.”

But even if a spinco’s carve-out financial statements accurately reflect economic reality at the segment level, it still doesn’t mean the fundamentals will continue to look the same after the spin-off is completed. We usually keep an eye out for two important factors which can change the financial profile of a spinco on a go-forward basis:

- Changes in Capital Structure: Spin-offs usually issue some debt around the time of the separation. Thus, these companies will incur incremental interest expense which is not captured in their carve-out numbers. It’s possible for unpredictable macroeconomic events to affect a spinco’s cost of borrowing. For example, a few years ago we were performing due diligence on a spinco operating in the highly cyclical construction space. This company planned to tap the capital markets for fresh debt financing in the weeks leading up to its separation. However, in February of 2016 (just days before the planned spin-off) U.S. markets became spooked by collapsing oil prices and China’s currency devaluation. The spinco got stuck with $525mln of new senior notes (equal to >2x EBITDA) bearing a painfully high 9.5% interest rate. Even worse, these notes weren’t callable until two years later (a grim reminder of what happens when the credit window goes from “wide open” to “slammed shut” in an instant). Investors who received shares in the new spinco panicked and rushed to cash out. Index funds with mandates to continue holding the parent company alone (but not the smaller spinco) created even more selling pressure. A short-term liquidity pocket — too many sellers and not enough buyers — led to wild volatility in the spinco’s stock, which fell 25% in the first two weeks of trading before rallying 85% over the next seven months.

- Public Company Costs: Administrative expenses associated with running a public company include things like Sarbanes-Oxley compliance, auditor fees, tax reporting, ERP, etc. These costs can easily add up to $10mln+ per year (or >100bps of operating margin for a spinco with $1bln in annual revenue). Many spincos also decide to relocate their corporate headquarters, which takes time and money. We once witnessed a specialty materials company with $930mln in revenue spend >$25mln in CapEx to move their corporate HQ from Allentown, Pennsylvania to Tempe, Arizona. Ironically, this same company pitched themselves as “asset light” during their spin-off roadshow (excluding the new office furniture, of course)!

What specific biases are reflected in a spin-off company’s financials?

- Loyalty to the Parent Company: “Carve-out financial statements are furnished for the spun-off entity by the parent [company’s] managers, who typically remain with the parent following the transaction and owe no fiduciary duty to the spinco,” says Wiebe. We were reminded of this reality a few weeks ago, during an in-person meeting with the CEO and CFO of a recently created spin-off company. The parent company had chosen to offload >$1bln of asbestos liabilities to the spinco, even though the liabilities had no historical ties to the spinco’s legacy operations. When we questioned how something so egregious could have possibly been allowed to happen, the spinco’s CEO shrugged his shoulders and said, “I was given no say in the matter. It’s what [the parent company] wanted, so that’s what they got.”

- Compensation Incentives Misaligned: After a spin-off takes place, the parent company’s management team usually treats the spinco like a discontinued operation. That is, when communicating with investors, they choose to focus exclusively on the go-forward strategy for the remaining firm. This often coincides with the release of a new set of multi-year financial targets for remainco (to which the incumbent managers’ compensation is usually tied) — creating an inherent conflict of interest. “Parent managers acting opportunistically are likely to favor pushing income-decreasing items down to the spinco, because they are more likely to be evaluated on the performance of the assets that will remain with the parent company following the transaction,” says Wiebe.

- The Kitchen Sink Effect: The phrase “kitchen-sinking” is sometimes used to describe an accounting strategy whereby companies lump all bad news/losses into a single period so they can start with a clean slate. We sometimes see a similar phenomenon at play when parent companies allocate historical costs to spin-offs. “Poor divisional performance is often cited as a motive for spinoff activity under the notion that if owned and managed independently, the division’s performance will improve,” according to Wiebe. “As such, carve-out financial statement users may be unsurprised by low reported profitability, making it easier for parent managers to push down disproportionate income-decreasing accruals to the carve-out level.” Spinco financial statements might classify some of these income-decreasing accruals as “restructuring” or “other one-time” charges. In our view, it’s worth it to figure out the nature of any obscurely labeled costs. A few months ago, during our routine analysis of an upcoming spin-off in the Health Care industry, we flagged several material accruals in the spinco’s income statement. For the most recent fiscal year, the company had reported $219mln of GAAP net income, inclusive of nearly $60mln of pre-tax accruals that were labeled “non-cash” or “non-recurring.” Rather than simply valuing the firm based on management’s preferred metric known as “Adjusted Net Income” (which conveniently excluded all the charges listed above), we needed to first understand how these charges would impact shareholder value on an ongoing basis. We concluded that roughly 1/3 (or $20mln) of the accruals were related to ordinary items, like stock-based compensation, which would indeed affect the value of our ownership stake over time. Despite management’s claims to the contrary, these costs were anything but negligible. In fact, they caused us to meaningfully discount our internal valuation of the firm.

How do these biases affect the quality of financial reporting for spin-offs?

This is where we get into the meaty part of Wiebe’s paper, where he argues that the biases listed above should call into question the overall earnings quality (“EQ”) of spin-off company financial statements.

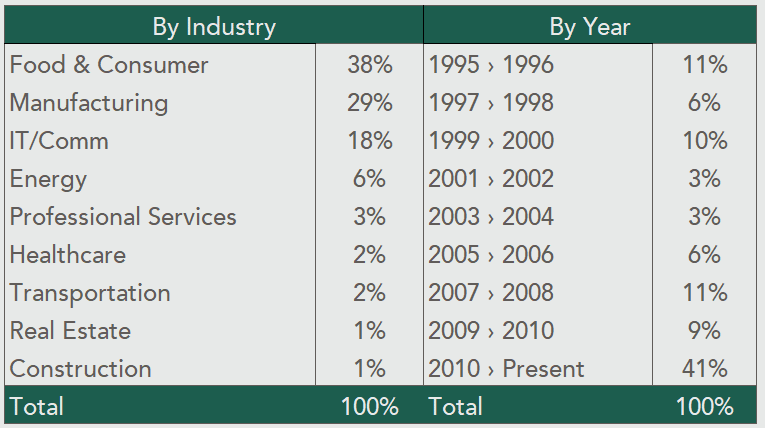

TABLE 1: Spin-off Companies Used in Wiebe’s Analysis

Source: Wiebe’s Statistical Analysis

Wiebe seeks to determine whether or not spincos’ carve out financial statements are (with a high degree of statistical significance) reliable indicators of post-spinoff earnings/cash flows. He analyzes a sample of 160 U.S. spin-offs that occurred between 1995 and 2017 (TABLE 1), and measures earnings quality by calculating total operating accruals for each spinco (i.e., the difference between reported net income and operating cash flows).

The financial statements of a company with high earnings quality should, in theory, contain very few operating accruals (such that net income plus D&A roughly equals operating cash flow). Meanwhile, the carve-out statements of spin-off companies — which Wiebe suggests are not high quality — should stand out against a control group due to the presence of “systematically more negative” accruals.

What do the empirical results show?

- Negative Spinco Accruals: “Spincos’ carve-out accruals appear to be more negative than peers’ accruals. Mean total operating accruals for spincos is -9% of lagged assets, which is significantly more negative than the -6% mean for industry peers.”

- Positive Remainco Accruals: “Spincos’ carve-out accruals are larger in absolute value (i.e., of lower quality) and more negative than the consolidated accruals from which they were carved out…This provides evidence that income-decreasing accruals are, on average, more likely to be carved out to the spinco than kept with the parent.”

- IPO Financials are Over-Hyped: “The absolute accruals of pre-IPO firms are much larger than those of the other control groups. In fact, the average [accruals] among pre-IPO firms is not statistically different from the mean of spincos’ [accruals]. However, unlike spincos’ mean [accruals], which [are] negative, the mean pre-IPO [accruals are positive] 3% of lagged assets. This is consistent with income-increasing earnings management before IPOs.”

- Spinco Financials are Often not Indicative of Future Performance: “…[T]he primary focus of financial reporting is earnings and its components (e.g., accruals), and an important objective of financial reporting is to provide information that is useful in predicting future performance and assessing the amount and timing of future cash flows. [The results suggest that] the predictive ability of carve-out earnings for post-spinoff cash flows is decreasing in the magnitude of carve-out accruals…[,] consistent with the idea that carve-out earnings with low total operating accruals are a better predictor of post-spinoff cash flows than carve-out earnings with high accruals.”

Why is this information relevant for fundamental investors?

Wiebe’s research implies that spin-off analysis might still be a job in need of the human touch. After all, a robotic trading strategy cannot predict future spin-off cash flows any better than a human if the historical carve-out financial statements themselves aren’t reliable. Numerous qualitative business aspects (e.g., management track record, employee satisfaction, industry position, underlying incentives, etc.) should also be emphasized in order to effectively determine what a spin-off company is truly worth. If one is made aware, for example, that the incoming CEO of a spin-off company nearly ran ran his or her prior firm into the ground due to irresponsible borrowing, what would be the best way to properly account for the likelihood of history repeating itself? Could such a probability be easily incorporated into an already-overly-complicated machine model? Maybe, but probably not without extensive time and effort, which in investing usually translates into massive opportunity cost.

All great investors fully understand that a company’s value is based solely on the future, not the past. However, these investors also accept that no one can predict the future with 100% certainty. The safest and most lucrative investment decisions are often not predicated on someone being 100% right about the future, but rather on that person’s ability to identify why everyone else (“the market”) is wrong. In today’s mechanical investing world, “everyone else” or “the market” sometimes lacks a clear understanding of what tomorrow holds, because their vision of tomorrow overly emphasizes recent events that occurred yesterday and today.

Here’s one analogy: picture the market as a winding racetrack upon which all market participants compete to cross the finish line first. However, imagine that most of your competitors driving in the race are only allowed to advance forward while looking into their rearview mirrors. Unlike you (a first-timer), they are forbidden from seeing out their windshields when they drive. They’ve competed in this race thousands of times and seem to have mastered the ability to navigate the course while looking backwards. But on this particular day, the sky darkens, and it starts to rain, making it very difficult for everyone to see. Your competitors lose track of where they are on the course and decide to pull over until the storm passes. They’ve never encountered bad weather before and think that it will surely blow over quickly. Meanwhile, you can see sunlight ahead in the distance, a signal that weather conditions will soon improve. You advance forward cautiously, cruising slowly through the rainstorm, until finally you reach the other side and have clear visibility of the racetrack again. By the time your competitors decide to get back on the road because they see sunlight re-emerge in their rearview mirrors, you’ve already gained an insurmountable lead in the race. And it all happened because you remained forward-looking while everyone else had their eyes glued on the past.

Tying the analogy above back into Wiebe’s research, spin-offs could be viewed as special situations when companies’ historical carve-out financial statements become muddied by numerous biases (“stormy weather”), making them unreliable predictors of the future. Rather than valuing a spin-off company based on the past or waiting to see proof that the company’s financials are improving (akin to pulling over and watching for the storm to clear in your rearview mirror), the optimal strategy might be to always keep your gaze forward in anticipation of how the road ahead will change.

Where can fundamental investors gain an edge?

John Maynard Keynes once wrote: “As time goes on, I get more and more convinced that the right method of investment is to put fairly large sums into enterprises which one thinks one knows something about and in the management of which one thoroughly believes.” Keynes essentially highlighted three rules of investing which we think are critical: (1) stay concentrated, (2) understand what you own, and (3) invest alongside trustworthy management teams.

In the case of spin-offs, we often find that the third condition (finding trustworthy managers) is the most difficult one to satisfy. That’s largely because many spin-off companies install a brand-new management team with no historical track record for investors to evaluate. During our research process, we remain constantly on the lookout for clues that are suggestive of how a spin-off company’s management team intends to run the business after taking the reins. Numerous hours spent pouring over earnings transcripts, listening to roadshow presentations, or even interviewing the managers directly, helps us construct a probability-weighted narrative of how the future could unfold (allowing us to understand why we as shareholders will be adequately compensated for the risk we assume).

When investing in spin-offs, it pays to listen. After all, it is senior management (not the analyst community) who ultimately decides how a company allocates its capital. As Buffett famously stated, “After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.” In order to predict how a company’s fundamentals will evolve, you must first gain a clear idea of management’s strategy and capital allocation philosophy. To illustrate this point, below are quotes from spin-off CEOs which we flagged as either “favorable” or “unfavorable” during our due diligence process.

Desired Attribute: An internal focus on free cash flow, rather than an obsession over questionable measures of business value (like EBITDA)

- Favorable Quote: “We’re pleased with the cash flow performance. We talked a lot about the markets here, and earnings and margins and so forth. But at the end of the day, cash is still king.”

- Unfavorable Quote: “And we have cultivated a model for EBITDA growth, which we expect to outpace revenue growth going forward.”

Desired Attribute: Evidence that management takes an opportunistic approach to allocating capital

- Favorable Quote: “We are very pleased with our ability to retire 5% of our shares at a very attractive valuation. And we are taking a pause on that, post acquisition, and putting priorities on paying down debt.”

- Unfavorable Quote: “We’ve got a great capital allocation methodology that will give us the EPS that’s showing growth. So that’s where we are.”

Desired Attribute: A management team who understands that more leverage means more risk

- Favorable Quote: “I think when we look at financial priorities and what we’re going to do with the cash, it’s pay down the debt, pay down the debt, pay down the debt.”

- Unfavorable Quote: “So we’re 5x levered with that synergy number we put in. Take that out and you’re closer to 6x. We’ve been intentional. As you all know, this is a very durable business, very much a kind of rules-based cash business.”

It’s interesting to ponder how an algorithm would interpret these nuanced quotations. If factors like EPS growth and EBITDA growth are generally regarded among investors as being positive indicators of value creation, then why do references to both of these metrics count negatively towards our opinion of the managers quoted above? The reason is because we prefer to invest alongside managers who think like owner-partners, not Wall Street analysts. We as shareholders are primarily concerned with how much true capital (i.e., cash flow) a company can consistently generate, and how management intends to allocate that capital over time for our benefit. In a world where interest rates globally are near zero, it’s easy for a CEO to deliver EPS growth by using borrowed money. It’s even easier to grow EBITDA, since this metric ignores financing costs as well as capital expenditures necessary to maintain a company’s asset base. (Generally speaking, the higher up you climb on the income statement, the more likely it is for reported numbers to become decoupled from economic reality.)

All spin-offs are unique in their own respect, and for that reason it is incredibly hard to standardize or automate the appraisal process for such companies. Carve-out financial statements are riddled with biases which lower the predictability of future cash flows, yet the amount and timing of future cash flows are the two most important drivers of business value. Fundamental investors should embrace this uncertainty and recognize that qualitative elements (like management commentary) can reveal a lot about what lies ahead for a spin-off company. As investors who thoughtfully weave together both quantitative and qualitative analysis, we expect to continue to find opportunities in spin-offs for years to come.

Mitchell Lolley, CFA

Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed reliable but is not necessarily complete. Accuracy is not guaranteed. Any views expressed are subject to change at any time, and Nixon Capital disclaims any responsibility to update such views. Portfolio holdings and sector allocations may not be representative of the portfolio manager’s current or future investment and are subject to change at any time. All charts and graphs are provided for illustrative purposes only. This information is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person without the prior consent of Nixon Capital LLC.