“I think you will find as we go along that much of what I have to say about hitting is self-education — thinking it out, learning the situations, knowing your opponent, and most important, knowing yourself.”

News and information about the world’s economy and markets has never been easier to come by than it is today. Yet amid the daily gush of news chatter, there is little of what I’d call “investment wisdom.” Therefore, it is an important job of the serious investor to regularly turn away from short-term news and financial gossip and instead turn toward sources of timeless investing wisdom. A manager of investments wants to make sure that decisions are made based on bedrock principles rather than fads and ephemera.

Oddly enough, when I wish to retreat to bedrock investing principles, I frequently return to a book from my childhood that wasn’t even written about investments. In fact, it’s a book about baseball: The Science of Hitting, written by Hall of Fame outfielder Ted Williams. He was baseball’s greatest hitter of the 1940s and 1950s, and I caught up with his book when I was a boy in the 1970s. When studied from an investor’s mindset, his book’s core principles illuminate concepts quite applicable to successful investing.

Williams approached hitting just the way the thoughtful investor should approach the craft of investing, with a healthy mix of analytical seriousness, intellectual curiosity and a love of the game. He displays an unwavering commitment to excellence and to constant improvement. He loved analyzing baseball and talking about its finer points, just as the best investors can’t help but immerse themselves in conversation and study regarding investing. As Williams writes in The Science of Hitting, “In my 22 years of professional baseball, I went to bat almost 8,000 times, and every trip to the plate was an adventure, one that I could remember and store up as information.”

Like a master teacher of any subject, Williams delivers advice using simple, understandable principles. But he then backs up the deceptive simplicity of the principles with significant philosophical depth and examples. Consider the three precepts in the book’s section entitled “Three Rules to Hit By.”

- Get a Good Ball to Hit

- Apply Proper Thinking

- Be Quick With the Bat

OK, sounds simple, though not necessarily profound. But Williams takes these three holistic commands and builds a comprehensive hitting philosophy from them. I’m here to make the case that a person devoted to intelligent investing can learn just as much from these rules as a ballplayer can. I’ll focus on the first two rules.

Rule 1: Get a Good Ball to Hit

The central tenet of Williams’ philosophy — “Get a good ball to hit” — is the foundation on which his teachings rest. And it can serve as an investor’s foundation as well.

When Williams preaches “Get a good ball to hit,” he’s counseling that a baseball hitter is going to get far more base hits if he waits for the pitcher to throw pitches in the strike zone. In contrast, when a jumpy, impatient batter reaches for pitches way outside the zone, he’ll usually swing and miss or hit the ball weakly.

Following this seemingly simple advice is easier said than done, whether for a ballplayer or an investor. Batters must face crafty pitchers throwing 88 mile-an-hour sliders that initially look devilishly attractive — but that end up several inches off the plate and are thus unhittable. Well, this is the story of investing as well. On a weekly basis, a manager of investments is very likely to see an investment recommendation or two (they even call them “stock pitches”) that initially look attractive — perhaps so seductive that he thinks of taking immediate action. But if the investor has the patience to not commit quickly but to continue to review and analyze the pitch, he will find that the majority of offerings don’t look quite as good once they get closer to the investor’s plate. And remember, an investor has an advantage a ballplayer doesn’t have. Whereas a batter can take only three strikes at bat before being called out, an investor is allowed to take as many pitches as he/she wishes before choosing a pitch appropriate for investment.

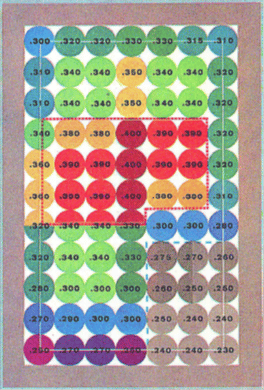

There’s an ingenious diagram on page 37 of The Science of Hitting that can help an investor stay disciplined and make money. It’s a full-page photo diagram showing Ted Williams at bat next to a box representing his strike zone. (This illustration is also on the cover of the 1972 edition that I grew up with. Note the $1.95 price tag in the upper right corner — a value investment, I’d say.)

Williams devoted himself to knowing his own strike zone. “My strike zone, almost to the inch, was 22 by 32, or 4.8 square feet,” writes Williams. Dividing his strike zone into segments the size of a baseball, he calculated that his strike zone was 7 baseballs wide and 11 baseballs high, allowing for pitches on the corners. From practice, experience and knowledge of his own weaknesses, he then applies a precise batting average to each ball in the zone. Those are the numbers you see printed on each colored ball. The result is a heat map detailing where Williams had probabilities in his favor — and where he didn’t. Example: The deep red circles in the belt-high, middle-plate area are assigned a .400 batting average, because he knew he had great odds when swinging at such pitches.

“My first rule of hitting was to get a good ball to hit. I learned down to percentage points where those good balls were. The box shows my particular preferences, from what I considered my “happy zone” — where I could hit .400 or better — to the low outside corner — where the most I could hope to bat was .230.”

This is the same “know thyself” probabilistic mindset that should be applied to investing. The intelligent investor just has to tap into the power of Williams’ work in math and probabilities, using the strike-zone map as a model for investing. The wise investor takes the time to ask himself, “Is this stock a low-risk ‘fat pitch’ in the middle of the plate with limited downside and more upside than the investments I already own? Or am I reaching to the very outside corner of the plate and forcing a swing at a low-probability phantom opportunity?”

Ted Williams was forever thinking about the math of winning ballgames and improving one’s batting average. Here’s how he describes the effect that selectivity at the plate can have on a ballplayer or a team:

“Now, if a .250 hitter up forty times gets 10 hits, maybe if he had laid off bad pitches he would have gotten five walks. That’s five fewer at-bats, or 10 hits for 35, or .286. And he would have scored more…because he would have been on base more.”

This is the practical daily math of winning ballgames. And it’s surely the math of better investing. The investor who can use selectivity to limit himself to high-probability (better batting average) investments over long periods of time is giving himself a mathematical advantage in the quest to compound capital at high rates over time.

A remarkable thing about The Science of Hitting and its application to investing is that you don’t even have to read every word of the short book to extract the value of Williams’ central tenet. Simply study and meditate on the strike-zone chart on page 37. As a boy, I spent hours on the orange bean-bag chair in my room (bean-bag chairs were cool in the 1970s) reading and re-reading The Science of Hitting, and I benefit to this day from having that diagram indelibly imprinted on my brain.

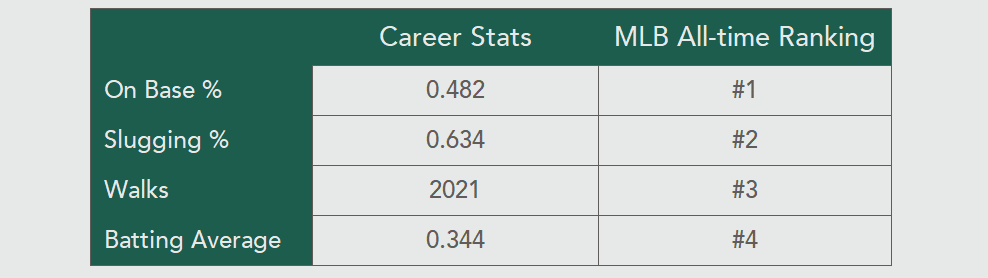

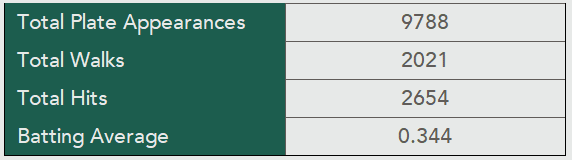

Ted Williams by the Numbers

Rule 2: Apply Proper Thinking

Anyone who follows sports has at one time or another observed a case of a talented, well-trained athlete who, despite a host of advantages, can’t be relied upon when the game is on the line. What’s missing for such an athlete is a mastery of the psychology of his or her sport. There is no competitive endeavor — investing and baseball included — that does not require mental toughness to achieve consistent results over prolonged periods. This is why Williams’ second rule is to apply “proper thinking.” He explains:

“Hitting a baseball — I’ve said this a thousand times, too — is 50 per cent from the neck up…All they ever write about the good hitters is what great reflexes they have, what great style, what strength, what quickness, but never how smart the guy is at the plate, and that’s 50 per cent of it.”

Williams believed that proper thinking derived from preparation. From repetition. From taking batting practice “until the blisters bled.” Williams also believed proper thinking was developed by learning from others, especially from observing and talking with experienced experts.

For Williams, these two aspects of developing proper thinking came together for him as a 20-year-old minor leaguer when he developed a spring-training friendship that year with the great Hall of Fame hitter Rogers Hornsby, the only player to ever hit 40 home runs and bat over .400 in the same season. Williams says he spent hours that spring “picking Hornsby’s brains for everything I could” in an attempt to learn from a master.

“And he’d stay out there with me every day after practice and we’d have hitting contests, just the two of us, and that old rascal would just keep zinging those line drives. Hornsby used to say, “A great hitter isn’t born, he’s made. He’s made out of practice, fault correction and confidence.””

Investors develop proper thinking the same way: through constant practice and by learning from others. “Practice” in this case means turning over a lot of stones in search of great stocks, reading all the public filings about prospective investments and talking to a lot of businesspeople. You must also devote ample time to analyzing a company’s financial numbers to put proper parameters on its valuation. And then the investor must, well, invest, in order to learn through actual experience how market forces create opportunities to, for instance, buy more shares at a discounted price or to see how an investment responds to earnings reports. Both investors and ballplayers must develop an almost autonomic level of pattern recognition so as to be constantly noticing, “I’ve seen this pattern before, and there’s an 85% chance that the following will happen.”

The “learning from others” part of developing proper thinking is especially easy for investors, because all one needs to do is read a lot. Read about business, read about industries, and read the books and writings of noted investors. Ted Williams didn’t have it so good in the 1930s — I doubt there were any books about how to hit a baseball back then.

Ted Williams Career Stats

Williams: A Goal-Setter and Risk Manager

If you reconstruct the career of Ted Williams by holding his lifetime statistics in one hand and his writings about baseball in the other, you can only conclude that he was a great goal-setter and a fine risk manager.

“I think every player should have goals, goals to keep his interest up over the long haul, goals that are realistic and reflect improvement. For me, if I couldn’t hit 35 home runs, I was unhappy. If I couldn’t drive in 100 runs, if I couldn’t hit at least .330, I was unhappy.”

Williams took those goals and pieced together a daily strategy for achieving them, a strategy that included active “risk-management” skills, to borrow a term from the investment world. If you read what he wrote, it’s pretty clear that he had a goal of striking out less than 50 times a year, despite his big swing. (He never struck out more than 50 times in a season past the age of 25.) This is a differentiated strategy for a power hitter. Many power hitters just want to rack up a lot of homers, regardless of how many times they strike out. Williams was different. He thought it was his job to hit home runs and to hit for average.

An investor can learn from this mindset. Sure, you want to own a few investments over the years that are home runs — they’ll come without effort if you fish in the right ponds. But the way the math of compounding works, it’s probably more important to limit “strikeouts” (investments that decline) than it is to slam homers.

In his book, Williams addresses all manner of risks that must be compensated for: how to hit with two strikes, how to hit when the wind’s blowing in your face, how to adjust to damp and rainy weather. You have to laugh at some examples, but I like the way he tries to think of every risk. He even details a strategy for what to do when you’re at bat and a cloud passes overhead and blocks the sun, temporarily decreasing the ambient brightness in the ballpark:

“Unless you know for a fact that your eyes can dilate quickly enough in the split second to adjust to a light that might be half the candle power, you’d be foolish to stand in there and try to hit. Step out and wait until the cloud passes, or until your eyes have dilated and are accustomed to the new light.”

This is a man who cared about every at-bat and left little to fate. Like a careful investor who doesn’t want to waste money, Williams didn’t want to waste at-bats. He’s thinking of risk-management strategies at all times. He’s not just crossing his fingers and waiting for the wind to be at his back (baseball’s version of a bull market).

In sum, we don’t just view The Science of Hitting as enjoyable summer reading. We analyze the words of Ted Williams because we want to develop a lot of ways to win. We study the tenets and have woven the book’s principles into the investment process for daily use. A visitor to our meeting room will see copies of Ted Williams’ strike-zone diagram on the wall, serving as a constant reminder to follow his central tenet: get a good ball to hit. Before making an investment, I find that it’s worth it to peruse the Williams diagram to ponder just how certain I am that the probabilities are on our side. We don’t want to reach outside the strike zone often.

I like to think Ted Williams himself might have gotten a kick out of knowing his principles were being applied to the cerebral world of investing. Though Williams is often portrayed as having been gruff and undiplomatic, it’s hard to argue with his achievements or his advancement of the teaching of the sport. I’m grateful to him for leaving behind a $1.95 gift that keeps giving, The Science of Hitting.

Investment wisdom can be found in some unlikely places.

Paul Moomaw, CFA

About the Book

The Science of Hitting

By Ted Williams and John Underwood

Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Copyright 1970, 1971, 1986 by Ted Williams and John Underwood

(The 1972 edition pictured was published by the Pocket Books division of Simon & Schuster)

Postscript: The Career of Ted Williams

Ted Williams played baseball for the Boston Red Sox from 1939 to 1960 and was one of the great hitters of all time. He was the last player to hit .400 or better for a season (1941), which means, of course, that he got a hit 40% or more of the time. Williams also pounded out 521 lifetime home runs and had 1,839 runs batted in. He had such a practiced eye at the plate and such a commitment to getting good pitches to hit that opposing pitchers walked him 2,021 times, which was more than 20% of his trips to the plate. This discipline of avoiding the temptation to swing at bad pitches contributed mightily to his lifetime on-base percentage of .482.

Amazingly, Williams racked up the above lifetime statistics despite missing five seasons for military service during his prime playing years between the ages of 25 and 35. He missed the 1943, 1944 and 1945 seasons to serve in World War II and later missed most of the 1952 and 1953 seasons serving as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. One can do a little “what if?” mathematics to see that if you added in the 2,500 or so trips to the plate that Williams missed for military service, he might have approached the 714 homer total hit by baseball’s legendary Babe Ruth. A key difference between Williams and Ruth is that Williams struck out only about half as often as Ruth.

Ever the student of baseball, Williams finished his career strong. At age 39, he batted .388 and walloped 38 homers. Even in his final season at age 42, he hit .316, finishing his career with — what else? — an eighth-inning homer blasted into the wind into the right field corner seats at Fenway Park. Later, around the time that The Science of Hitting was published, Williams began a four-year stint as a major league manager. He was manager of the Washington Senators for three years, and he was the Texas Rangers’ first manager when the Senators franchise moved to Texas in 1972. Williams died in 2002.

Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed reliable but is not necessarily complete. Accuracy is not guaranteed. Any views expressed are subject to change at any time, and Nixon Capital disclaims any responsibility to update such views. This information is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person without the prior consent of Nixon Capital LLC.